Close Encounters of the Nerd Kind

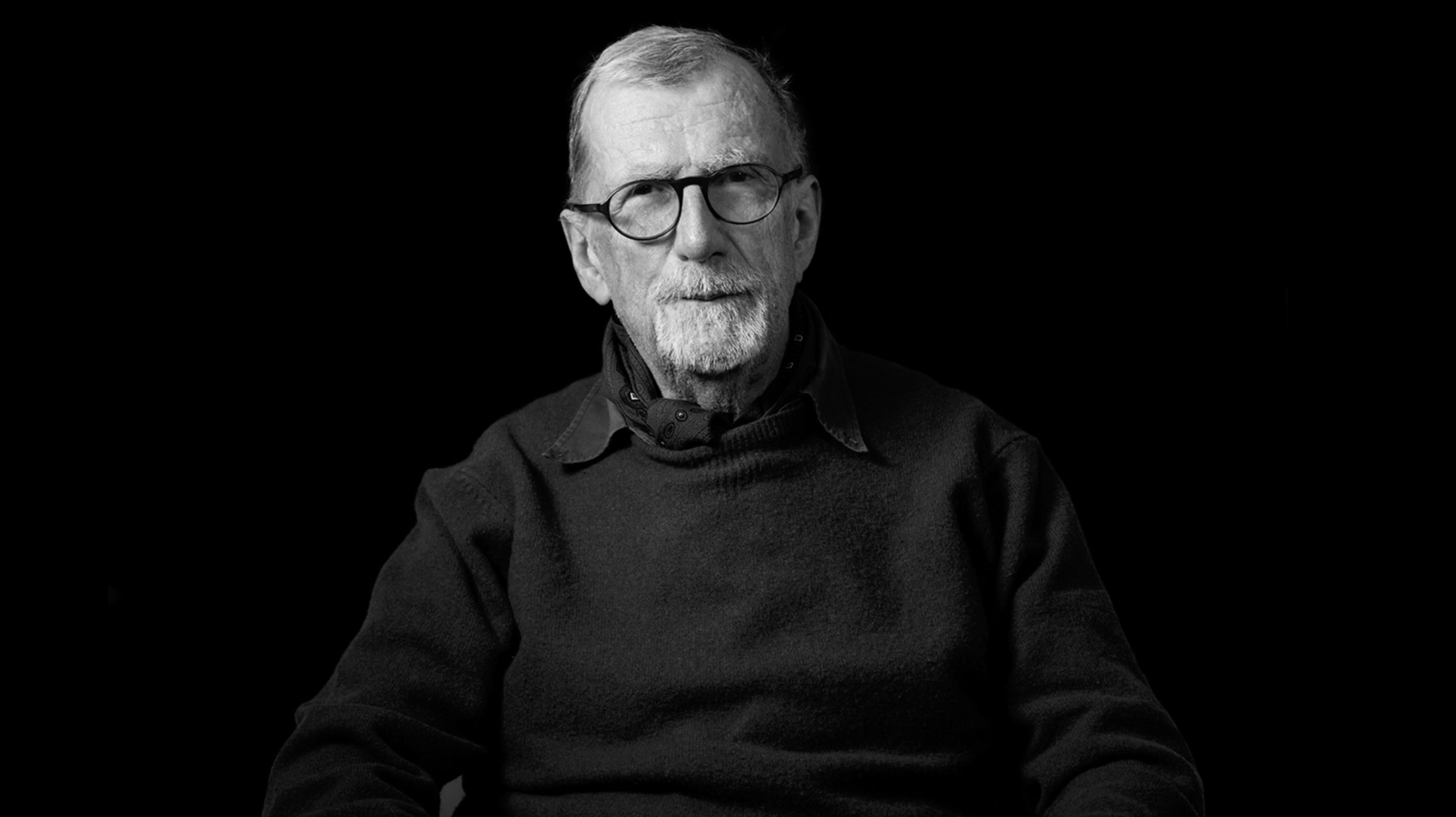

Imagine feeling concurrently bamboozled and enlightened, bewitched and transfixed, alienated and attracted. That’s how I felt the first time I saw Bruno Latour speak in person. I was a second year doctoral student specializing in Science Education and living in Michigan. It was 2006.

First Encounter

I attended Latour’s lecture at the urging of a notable University of Michigan education professor, Jay Lemke, who had stressed to our doctoral class that a scholar and intellectual of significant importance was soon to give a public lecture as part of the University’s Rackham Lecture series. That important scholar-intellectual was Bruno Latour.

Latour’s invited lecture was titled, “First and Second Empiricisms,” and he opened the talk by projecting the peculiar image of a contented medical artist seated in a white-tiled, sterile-looking, well-lit room. The artist appeared to be drawing a human cadaver’s severed and desiccated arm, which was disinterestedly resting on a cloth-covered specimen tray; it was positioned in such a way that its former owner might be interpreted as pridefully displaying a wedding ring for the attentive artist.

I sat within the first twelve rows of the auditorium not far from the projected image, but also from Professor Latour himself, who was positioned to the side of the stage and standing beside a podium. Sitting next to me was Steve—a close friend and fellow doctoral student in my Ph.D. program. In the minutes following the lecture’s conclusion, I vividly remember experiencing powerful yet contradictory emotions. On the one hand, the freshness and novelty of Latour’s ideas were deeply enchanting; on the other, the depth and breadth of his ideas made them frustratingly confounding. Stumbling out of the amphitheater, Steve and I both agreed: we felt as though we had grasped precious little of the true substance of Latour’s presentation, and yet, we each felt a strong urge to latch on to more of what we had been unable to seize during Latour’s lecture.

Once we reached Steve’s car to begin our drive home, and almost as if he were guarding a well-kept state secret, Steve divulged that he had recorded Professor Latour’s lecture on his laptop, keeping the top cover partially open throughout the talk. Although the resulting audio quality was poor, Professor Latour’s voice, nevertheless, kept us company through Steve’s laptop speakers for the entire 60-minute drive home. Even after a second hearing within a single evening, however, we both still felt as though we were no closer to corralling the precious puffs of anthropological, sociological, and philosophical clouds cast adrift by the esteemed Professor Latour into the Rackham Auditorium on that autumn evening in Ann Arbor.

Second Encounter

Had that autumn evening been my last encounter with Bruno Latour, I’m not sure I would have had the tenacity—or the courage—to pursue his ideas to the extent I have for (almost) the past 20 years. As fate would have it, though, a week after Latour’s campus visit Professor Lemke assigned our class several chapters to read from Latour’s groundbreaking book, Laboratory Life, which he co-authored with the British sociologist Steve Woolgar. It turns out Laboratory Life was like nothing I had previously encountered either in or outside of graduate school.

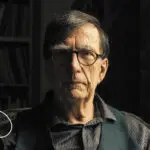

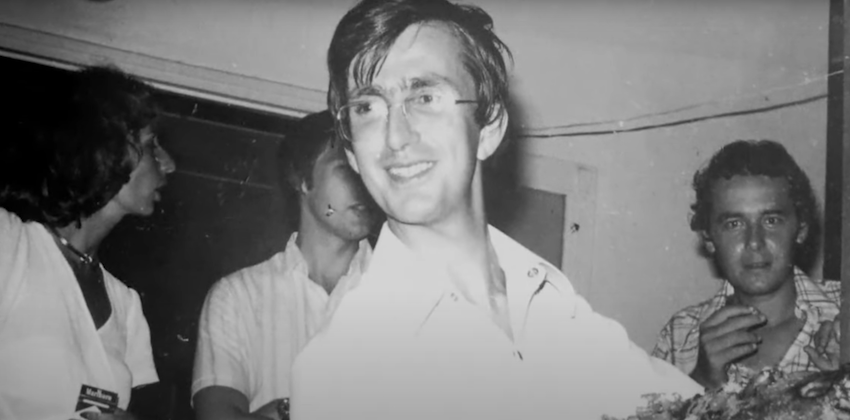

For those unfamiliar with this classic 1979 text (to which a second edition was added in 1986), think of the iconic image of an anthropologist at work in the field. If, as I am, you’re of the monthly, print-based National Geographic magazine generation, you’re most likely imagining an adult man or woman wearing glasses, holding a notebook, dressed in loose-fitting, khaki-colored clothing, embedded in a remote setting, and studying remote peoples dressed quite differently than the anthropologist.

It’s quite possible you’ve conjured an image resembling something like this…

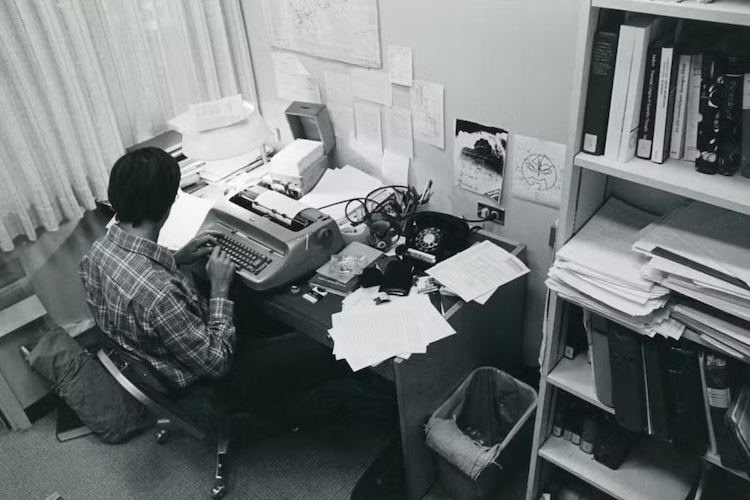

What you wouldn’t likely have conjured is an image of an adult man or woman (still wearing glasses) surrounded by telephones, typewriters, documents, and books, and embedded within a prestigious Southern Californian scientific laboratory, studying highly modern people (scientists!) dressed quite similarly to the anthropologist.

In other words, when asked to think of a field anthropologist at work, you almost certainly would not have conjured an image like this…

As Professor Lemke would later explain to our doctoral class, therein lies Latour and Woolgar’s innovation: just as field anthropologists turn their gaze toward remote cultures in the high Andes, Amazonian basins, and rainforests in the Malay Archipelago, in Laboratory Life Messrs. Latour and Woolgar turn their anthropological gaze toward a nearby culture—a tribe of first-rate endocrinologists occupying a Nobel Prize-winning laboratory in coastal California. With this novel pivot, Latour and Woolgar produced one of the first (and to this day still one of the most well-known) examples of an anthropological study of modern science (1).

In a position such as his, Jay Lemke knew well that science teacher educators and science education researchers must look to all sorts of science-observant disciplines to enrich and inform their work—e.g., the history of science, the philosophy of science, and the sociology of science—but Jay wanted us to know there was also a frequently overlooked anthropology of science to lean into, and my sense back then was that he wanted to make sure his doctoral students gave serious consideration to Latour’s anthropological—and philosophical—work upon finishing his course.

For my part, seduced by the idea of using anthropological methods to investigate both teaching and learning science, I decided to write my final course paper on Laboratory Life, and Jay’s course set me on an intellectual path I’ve rarely strayed from since. My 2013 Ph.D. dissertation was, in fact, a comparative anthropological study of sorts. Of a small tribe of university-based scientists I asked a Latourianesque question: What material, historical, and practical conditions are enacted when producing scientific understanding in field settings via ‘research,’ and how are these similar to—and different from—the conditions enacted when producing scientific understanding in classroom settings via ‘teaching’?

Following Bruno Latour to West Africa

For years after first seeing and reading Bruno Latour, I often wondered how he and Woolgar arrived at the novel anthropological approach they took in Laboratory Life. After many years of mapping Bruno Latour’s work and movements myself—but also because of the fine work done by many contemporary Latour scholars such as Anders Blok, Torben Jensen, Gerard de Vries, and Henning Schmidgen—I can now say with some confidence that to locate the beginnings of Latour’s anthropological disposition we must follow him to Africa, to the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), where he spent the years between 1973-75 working for the Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique Outre-Mer (ORSTOM), a developmental aid agency.

Required by French law to give either two years of military service or the equivalent years of national service to a “cooperative” (a sort of French Peace Corps), Latour went to the Ivory Coast with an invitation to study, “which factors are responsible for the fact that managerial positions are not filled with Ivoirians but with people from France or other Western European countries” (Schmigden, 2015) or, as another Latour scholar describes it more precisely, “to contribute to a study on the problems encountered when replacing white executives with local, black Ivory Coast managers” (de Vries, 2016).

It is actually in the final 1974 ORSTOM report Latour co-wrote with a colleague (Amina Shabou) that we find Latour’s first salient contribution to my personal domains of interest, namely, to science education. So, in the next Dear Bruno issue, we will take a closer look not at Latour’s time spent surrounded by prize-winning endocrinologists on the West American coast, but instead—just two years prior to career-propelling residency in the San Diego laboratory—at his time spent surrounded by European and Ivoirian industrial sector executives, directors, and workers on the West African coast.

Although it may seem counterintuitive for a science educator to look away from Laboratory Life for disciplinary insights and inspiration, I can assure you this temporary-but-necessary distraction will prove time well spent (2). Unlike other chroniclers who’ve skillfully illuminated various sociological, anthropological, and/or philosophical dimensions of Latour’s West African industrial research, in Issue No. 002 I will endeavor to re-describe his Ivory Coast work with an eye towards eliciting its most promising and powerful pedagogical dimensions, many of which continue to serve as foundational elements in my ongoing work within science education.

Bibliography

This Dear Bruno issue draws from the following primary sources (ordered chronologically):

— Blok, Anders. & Jensen, Torben E. Bruno Latour: Hybrid Thoughts in a Hybrid World. New York: Routledge, 2011.

— Schmigden, Henning. Bruno Latour in Pieces. New York: Fordham University Press, 2015.— de Vries, Gerard. Bruno Latour. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2016.

Notes

(1) Laboratory Life was also a foundational work for the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS).

(2) Laboratory Life will still be a focal text for numerous future Dear Bruno issues.